This is part of a blog series highlighting how water data is being put to use to protect freshwater.

In July 2022, community members gathered in Eel Ground, New Brunswick for a crash course in calibrating multiparameter probes and collecting aquatic bugs. It was just one of a series of Atlantic Water Network (AWN) bootcamps informed by DataStream insights.

For nearly two decades, the network has been helping 100+ water monitoring organizations across Atlantic Canada track the health of their watersheds. Now they’re targeting their support even more strategically, thanks to Atlantic DataStream.

AWN has served as the regional lead of the data-sharing hub since it launched in 2018. “Our communities really latched onto it and saw the value right away,” says Laura Chandler, AWN’s program manager. To date, the platform has logged more than five million unique measurements across the region. But there are gaps.

AWN’s Nova Scotia bootcamp. Photo: Atlantic Water Network.

Pinpointing data deficiencies

In 2019, AWN undertook a “sufficiency analysis,” examining data on Atlantic DataStream and drilling down to identify watersheds where data is lacking at a local scale. “It was a little different than just looking at a map view and seeing where there are clusters of data,” Chandler explained. “We tried to identify what it meant to have sufficient water quality data.”

Through extensive consultations with network members and countless hours hunkered down at her computer, Chandler created a tool that allowed them to adjust how much data is considered enough, based on local context. In some areas, that might mean monitoring 10 different parameters six times a year. Elsewhere, it might just mean tracking summer temperatures.

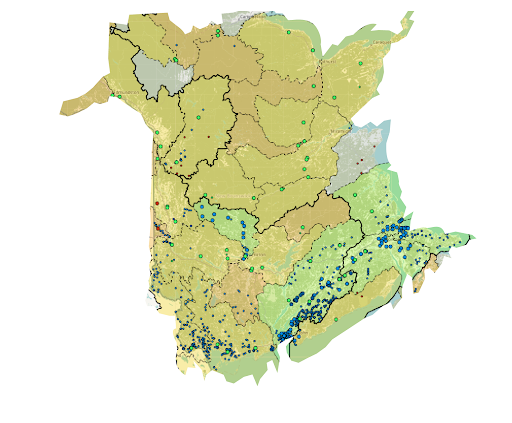

The resulting maps highlighted the watersheds that are rich in data, typically thanks to consistently funded and coordinated community-based monitoring efforts. In addition, decades of government monitoring data becoming open and accessible on DataStream contributed to these data-rich watersheds. The maps also showed areas with spottier data, often due to short-term, project-based funding that made consistent efforts more difficult.

One of AWN’s data sufficiency maps.

This work was inspired by WWF-Canada’s Watershed Reports, which showed that six out of Atlantic Canada’s 13 sub-watersheds lacked the data required to assign a water quality health score. AWN’s maps complement the Watershed Reports, adding the local monitoring context and zooming in to a regional or local level.

AWN also found there were areas with little to no sufficient data at all. That wasn’t surprising in rural and remote areas. But the deep dive also revealed gaps in places like Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton and Northern New Brunswick, where local environmental groups were doing great work. So Chandler launched more consultations, assessing local capacity in those “insufficient” areas.

In some, she found groups that were conducting water monitoring. But because they weren’t linked with DataStream yet, their data wasn’t getting shared more broadly. In other areas, cottagers’ groups and environmental organizations were interested in tracking water quality but didn’t know how to get started.

The Miramichi water monitoring bootcamp. Photo: Atlantic Water Network.

Delivering data-driven support

Armed with these insights, AWN targeted their outreach and programming where it was needed most.

They started with existing water monitoring groups, offering one-on-one support to familiarize them with the DataStream platform. For groups that weren’t currently monitoring, AWN set up regional equipment banks that loan out water kits and multiparameter probes at no cost. They also provided hands-on field training through bootcamps like the one in Eel Ground.

Chandler knows that capacity building takes time. But she’s inspired by the growing number of rubber-booted volunteers and community members stepping up to monitor the health of their rivers and lakes.

“I love our communities,” she says. “Seeing how passionate they are makes me more passionate about supporting them.”