This is part of a blog series highlighting how water data is being put to use to protect freshwater.

Lake Winnipeg’s watershed spans nearly a million square kilometres across four Canadian provinces and four U.S. states. Each spring, when the snow melts across that vast territory, it carries a tsunami of phosphorus into the lake. And that’s a big problem.

Phosphorus is a nutrient found in things like livestock waste, fertilizer and sewage. On land, it helps plants grow. In aquatic environments, it fuels an explosion of algae. In many cases, that algae is toxic to humans and pets. It makes beaches un-swimmable and boating difficult. And it’s bad for the province’s goldeneye, perch and other fisheries — harming fish directly through toxins and indirectly when the algae decompose, a process that consumes the oxygen that fish rely on.

So, in 2005, concerned citizens established the Lake Winnipeg Foundation (LWF) to boost the health of the world’s 10th largest freshwater lake. “We are a membership-based organization that is also guided by the expertise of a Science Advisory Council,” says Chelsea Lobson, programs director at LWF. “We are uniquely positioned to link science and action.”

An important way they do that is through community-based monitoring. In 2017, LWF set up a network of volunteers and teamed up with conservation partners to monitor smaller tributaries like the Seine River that aren’t regularly monitored by governments. Armed with test kits, they capture crucial data during snowmelt and heavy rainfall events that can wash more phosphorus into the lake.

Volunteers sampling water at Truro Creek in Winnipeg, MB. Photo by Paul Mutch.

The program has proved a big success, identifying hotspots where high concentrations of phosphorus are found year after year. That data gets fed into Lake Winnipeg DataStream, an open-access platform that volunteers have embraced as a way to share their water quality data. Lobson says using DataStream is intuitive, and it’s easy to track trends. But what excites her most about DataStream is how it can inform decisions.

For years, LWF has been encouraging governments, funders and communities to use the community-based monitoring data on DataStream to target actions to phosphorus hotspots where they will have an impact. Last year, the foundation realized they needed to take their own advice. So, when staff and board members started to put together their 2023–2027 strategic plan, specific focus was put towards modelling this evidence-based approach as they established priorities.

One of those priorities is to better understand what’s driving high phosphorus loads in persistent phosphorus hotspots — whether it’s livestock agriculture, fertilizer use, municipal sewage or other activities. “Currently, our data tells us where the phosphorus is coming from,” Lobson explains. “But it doesn’t say what is causing those loads.”

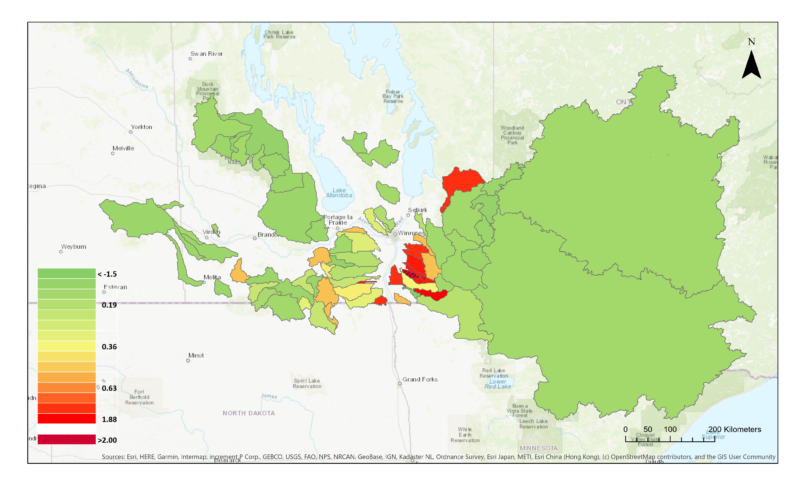

Phosphorous export map (kg ha y), 2019. Map by Lake Winnipeg Foundation.

So LWF aims to collaborate with academic researchers and government partners, correlating land use information with community-based monitoring data. “We’ve started to increase our capacity within persistent phosphorus hotspots, as well. This includes adding our own flow-metered sites to increase our data resolution,” explained Lobson.

With the resulting insights, the foundation can make recommendations on how to reduce phosphorus loads, transforming a massive watershed-wide challenge into a manageable list of issues to address.

Lobson joined LWF to create that kind of impact on water health. Like many Manitobans, her connection to Lake Winnipeg runs deep. She recalls childhood summers at her grandpa’s cottage, building sandcastles and walking along the seemingly endless shoreline.

“It’s a really beautiful place,” she says. “There’s a reason that so many people are working to protect it.”