“Modern treaties allow the Crown and First Nations to have a discussion about how to crystallize and represent the rights, titles and interests that First Nations citizens generally speaking in Canada have. It allows them to negotiate what they consider to be a fair understanding and adopt a set of principles and processes that is entrenched within a treaty right. Once it’s entrenched under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 it’s clear that no other laws of Canada, including the Constitution of Canada, could be in conflict with that, so it adopts certainly a supremacy that’s required and I think that’s why they have been important and will continue to be important.” Dave Joe, Negotiator (Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement)

This article is a reflection on the Treaty Negotiation and Implementation Simulation, an event organized by The Gordon Foundation, in collaboration with the Land Claims Agreements Coalition and other partners, aimed at engaging emerging Indigenous leaders in their modern treaties.

Modern treaties are playing an important role in shaping the relationships between Indigenous Peoples and Canada. Since 1975, 26 modern treaties have been successfully negotiated, providing Indigenous ownership of more than 600,000 km² of land. Many more modern treaties will be signed in the coming years, defining land rights of many more Indigenous Peoples and creating paths toward self-determination.

Modern treaties are binding reciprocal commitments between Indigenous, federal, and provincial or territorial governments. For Dave Joe, who negotiated the Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement, they are important in resetting the nation-to-nation relationship between Indigenous Peoples and Canadian governments:

These are not just concepts that float up there. They are constitutional concepts that are enshrined and entrenched. If there’s a breach in that, it allows the First Nations parties to proceed to court in the event that it’s not resolved through mediation or other processes. It keeps the parties more or less honest with respect to what their intentions were when they crystallized those rights in a modern treaty context.

Signing a modern treaty is a tremendous feat. Negotiations often take decades, and their completion is followed by a challenging implementation process intended to ensure that an agreed upon vision becomes reality. There are many lessons to be learned from negotiators, Elders, and others who worked for years on their treaties. Many modern treaty negotiators came of age in the 1970s and 1980s and are retiring or passing away. Their knowledge is at risk of being lost unless it is preserved and transferred to future generations.

In 2017, The Gordon Foundation responded to concerns of former and current negotiators and Northern experts working on modern treaty implementation that Indigenous youth were not engaging in modern treaties to the extent possible, and that something needed to be done. With a significantly large and growing young population, Indigenous youth have an important role to play in implementing their modern treaties.

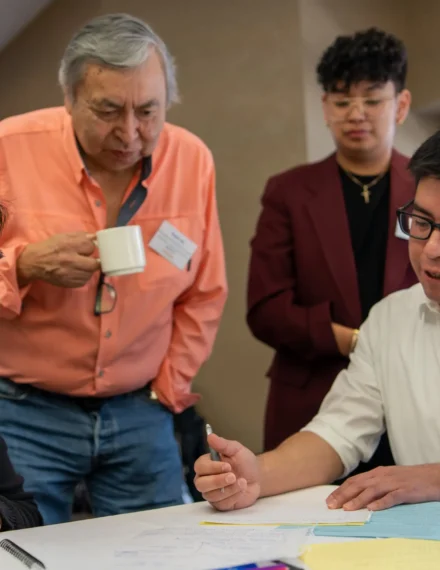

Participants in the Modern Treaty Negotiation and Implementation simulation.

John B. Zoe, who negotiated the Tlicho Land Claims and Self-Government Agreement, believes that if youth do not get involved, the spirit and intent of the hard-fought treaties will be lost. Such a loss could have unintended effects on the gains modern treaties are intended to make in areas such as resource rights, self-governance and environmental stewardship.

According to Dave Joe, treaty rights and the negotiation process are important for youth to learn because “this is going to be the world that circumscribes their rights, titles and interest…to maximize it, certainly to protect it, and to advance it they certainly will have to learn what those values are and what their rights are and how to best protect them in a fashion they understand.”

For over 30 years, The Gordon Foundation has been working with the North to amplify Northern voices. As a longstanding partner, The Foundation was asked to document existing programs, curricula and initiatives that engage and teach Indigenous youth and Canadians about historic and modern treaties. This led to the development of a report, Treaty Negotiators of the Future, which was informed by discussions with Northern experts, a consultation with participants at the 2017 Land Claims Agreement Coalition (LCAC) conference, and a three-month mapping exercise. Over 50 educational initiatives were documented, including courses for students from kindergarten to university, radio shows, games and films. The resources are now available as a portal that can be added to on the LCAC website.

The report also listed knowledge transfer as a gap and recommended that creating simulations for youth is an effective way to engage Indigenous emerging leaders in modern and historical treaties. Other innovative ideas include podcasts and internships.

Podcasts allow knowledge to be shared in a way that is accessible to a wider audience. A podcast series on treaties could facilitate pan-Canadian discussion on the overarching importance of treaties, while still allowing for regional nuances. It would provide insight and analysis of the potential for treaties to further self-determination, its limitations, and complementary strategies.

Internships would also provide an opportunity for emerging leaders to be present at the table, partake in conversations, be active in research and have access to the entire negotiation process. Internships would allow first-hand learning on the creation of a land claims agreement.

In response to these innovative ideas, The Gordon Foundation, in collaboration with the LCAC and other partners, organized the first Canada-wide Treaty Negotiation and Implementation Simulation for emerging Indigenous leaders. From February 28 to March 2, 2019, 17 next generation Indigenous leaders met with experts and former negotiators to expand knowledge and skills in the modern treaty process. Participants came from across the country, including Tsawwassen First Nation, Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Chek’tles7et’h’ First Nation, Ucluelet First Nation, Nisga’a First Nation, Taloyoak, Nunavut, Tłı̨chǫ First Nation, James Bay and Northern Quebec Cree, Gwich’in First Nation, Little Salmon Carmacks First Nation, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, Champagne and Aishihik First Nation, Ta’an Kwäch’än First Nation, and Selkirk First Nation. They ranged from 17 to 35 years of age and brought with them strong visions for their communities.

“Youth are inheriting these land claims and agreements. A lot of people always say youth are the future, but we’re here right now and

we’re willing and able to contribute to the betterment of our society.” Cecile Lyall, participant at The Gordon Foundation’s Treaty Negotiation and Implementation Simulation

Throughout the simulation, the participants were guided by John B. Zoe, Dave Joe, Dr. Joseph Gosnell (Negotiator, Nisga’a Final Agreement) and Danny Gaudet (Negotiator, Delıne Final Self-Government Agreement). Between the 1970s and 2000s, these individuals played pioneering roles in the development of modern treaties or self-government agreements for their nations.

The simulation was designed to build inter-generational connections and transfer knowledge from negotiators to new leaders who will play crucial roles in redefining the relationship between Canada and their communities and nations. It aimed to increase Indigenous emerging leaders’ interest in their respective modern treaties, and introduce them to treaty implementation and negotiation practices, issues, dynamics, and implications as one tool among others for self-determination.

Dave Joe believes the simulation “reflected the realities that First Nations live with when the Crown imposes constraints in a modern treaty context.” On the first day of the simulation, participants engaged in insightful discussion with the negotiators, representatives from the federal government and legal experts. They spent the second day negotiating a section of a wildlife harvesting and management chapter of a mock modern treaty. On the third day, they negotiated the implementation plan for the section negotiated by a different group. Everyone had a turn representing a negotiator from an Indigenous organization and the federal or territorial government.

Asya Touchie from Ucluelet First Nation, B.C. explains her group’s ideas for a section of a fictitious land claims agreement.

Twenty-six-year-old Cecile Lyall from Nunavut said she found the simulation very helpful, especially in terms of seeing treaty negotiations from all perspectives. “During the simulation, you sat on both sides. You can’t always just be the Indigenous group, so I found it very conflicting but enlightening to see it from the other perspective,” she said of her experience being a Canadian government representative. “I struggled with it because I thought, ‘Oh you’re the Indigenous group, I’ll just give you everything you want,’ but that’s not how it works.”

According to the participants, the simulation piqued their interest in their modern treaties and motivated them to get involved in implementation. It also built their skills in negotiation, public speaking, working in teams, and critical thinking. It provided knowledge transfer from the negotiators, and offered learning about different perspectives on negotiating. They also built connections across Canada. According to Lyall, the simulation was “very motivating” and having access to veteran negotiators was inspiring.

The simulation was historic: it was the first of its kind, and, according to John B. Zoe, offered much needed knowledge transfer that has been ignored for too long. “Anything we do in knowledge transfer is needed,” he said, adding that his generation was a quiet one and he sees less encumbrances on today’s Indigenous youth born under self-government. “There are better opportunities and potential for economic development, and not having everything administered from the outside. The simulation gave people experience.”

Lyall said, “It was very inspiring as a young person to try to foster the rights we have now and also fight for more political power within our regions…I’m from Nunavut, so I’m a Nunavut beneficiary and it really inspired me and gave me a sense of understanding of how hard it must’ve been. Nunavut turned 20 but the negotiations were not only 20 years ago – it was 50 years ago that they started negotiations. It was a very different time. I really envisioned their sheer determination to power through all those prejudices of the time and to really fight for what they believed in.”

For his part, Dave Joe believes that it is integral for Elders and people with experience to reach out directly to youth. “It’s incumbent upon people like myself to reach out to them, speak at colleges and impress upon them the importance.”

Lyall believes that it is a very important time to start these conversations around knowledge transfer. “A lot of the large comprehensive claims took quite awhile and the individuals that sat at the negotiation tables are aging and a lot of them are passing on, so right now it’s a really important time to ensure that the transmission of knowledge is happening and is passed down to younger generations…The Gordon Foundation is playing a key role in making sure that knowledge survives.”

Since the first simulation, The Foundation has received growing interest to run others in specific regions, to organize annual Canada-wide simulations, and to produce a toolkit of the simulation curriculum. There is also interest in other recommendations identified in the report, “Treaty Negotiators of the Future,” including a podcast on treaties across Canada, and internships for next generation Indigenous negotiators and implementers. The Foundation hopes to continue to work with Indigenous Nations interested in this work, and is currently exploring partnerships to ensure that knowledge-transfer and experiential learning tools on treaties are available and impactful across Canada.

Sherry Campbell is President and CEO of The Gordon Foundation.

This article was originally published by Northern Public Affairs.